Signal/Noise Video / Old Friends Gallery / Chicago, IL

Signal/Noise Video (detail)

Terroir / Land + Sky / Oxnard, CA

Terroir / Land + Sky / Oxnard, CA

Terroir (detail)

In The Groves / Land + Sky / Oxnard, CA

In The Groves / Land + Sky / Oxnard, CA

In The Groves / Land + Sky / Oxnard, CA

In The Groves (detail)

Intermezzo / Private Office / Washington D.C.

Intermezzo (reverse view)

Intermezzo (detail)

The Witness / Bert Green Fine Art / Chicago, IL

The Witness / Bert Green Fine Art / Chicago, IL

Watershed / University of Michigan Museum of Art / Ann Arbor, MI

Watershed / University of Michigan Museum of Art / Ann Arbor, MI

Beyond the Frame / Museum of Contemporary Photography / Chicago, IL

Beyond the Frame / Museum of Contemporary Photography / Chicago, IL

Dissolution / Bert Green Fine Art / Chicago, IL

Dissolution / Bert Green Fine Art / Chicago, IL

Sanctuary / 69th Street Red Line Station / Chicago Transit Authority

Sanctuary / 69th Street Red Line Station / Chicago Transit Authority

Sanctuary / 69th Street Red Line Station / Chicago Transit Authority

Anthem / Klompching Gallery / Brooklyn, NY

Anthem / Klompching Gallery / Brooklyn, NY

Reverb / Indiana University Northwest School of the Arts / Gary, IN

Reverb / Indiana University Northwest School of the Arts / Gary, IN

Reverb / Indiana University Northwest School of the Arts / Gary, IN

Nature Now / Lubeznik Center for the Arts / Michigan City, IN

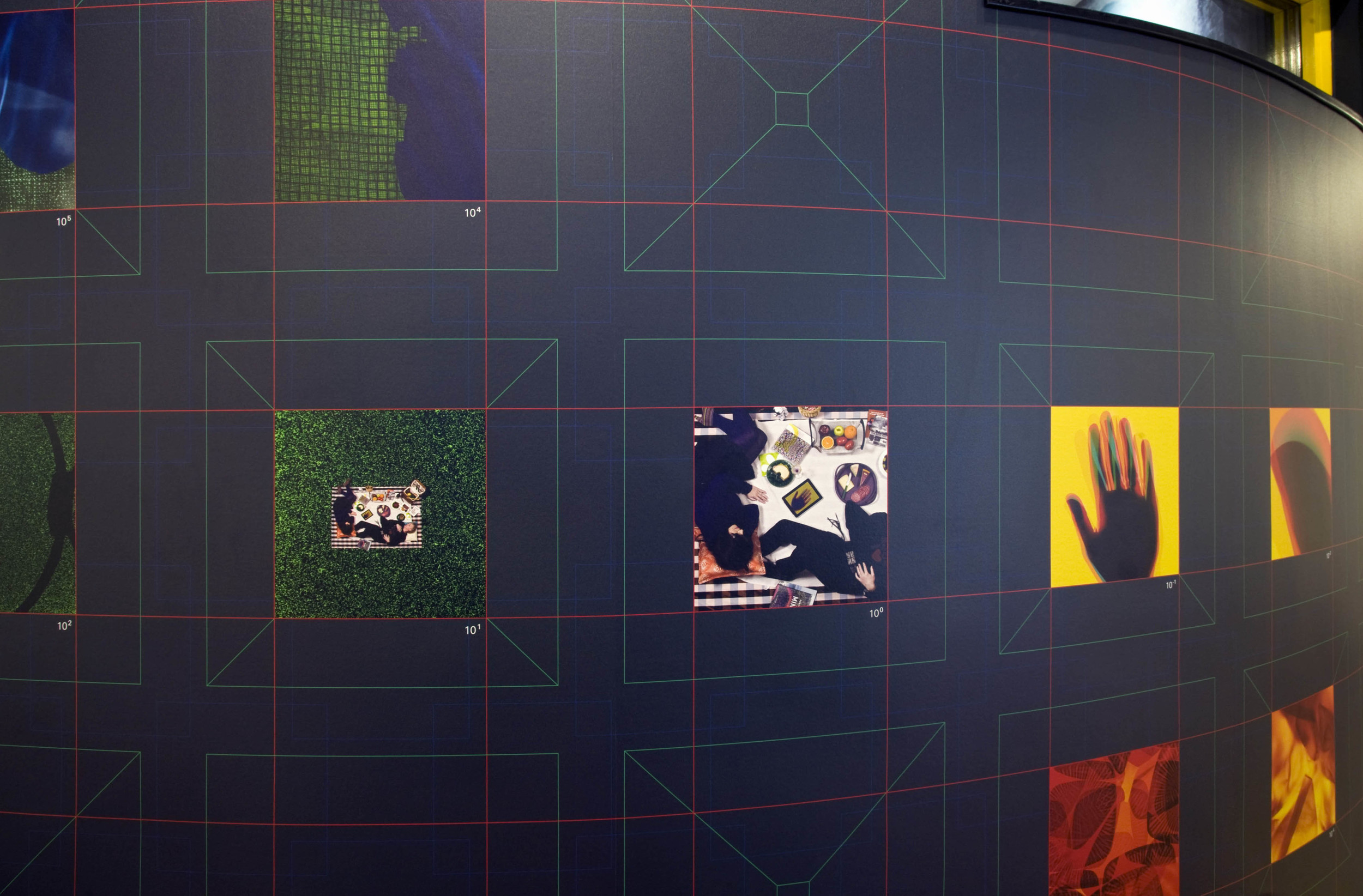

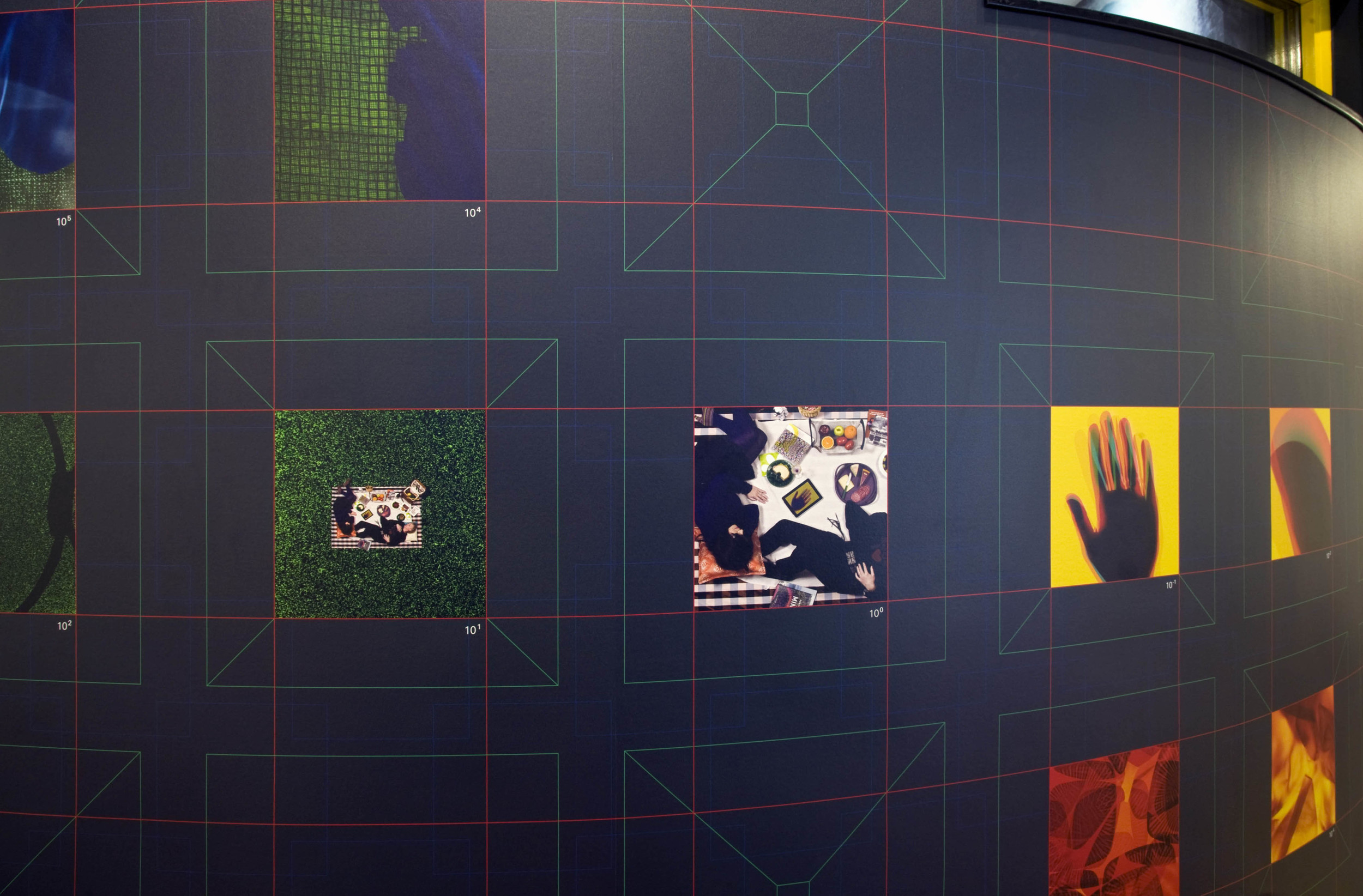

On Plane View / Klompching Gallery / Dumbo, Brooklyn

On Plane View / Klompching Gallery / Dumbo, Brooklyn

Bauhaus und die Fotografie / NRW Forum / Düsseldorf, Germany

Bauhaus und die Fotografie (detail)

Metric 1:50 “Touchstones” / Para Foundation / Berlin

Metric 1:50 Touchstones (detail)

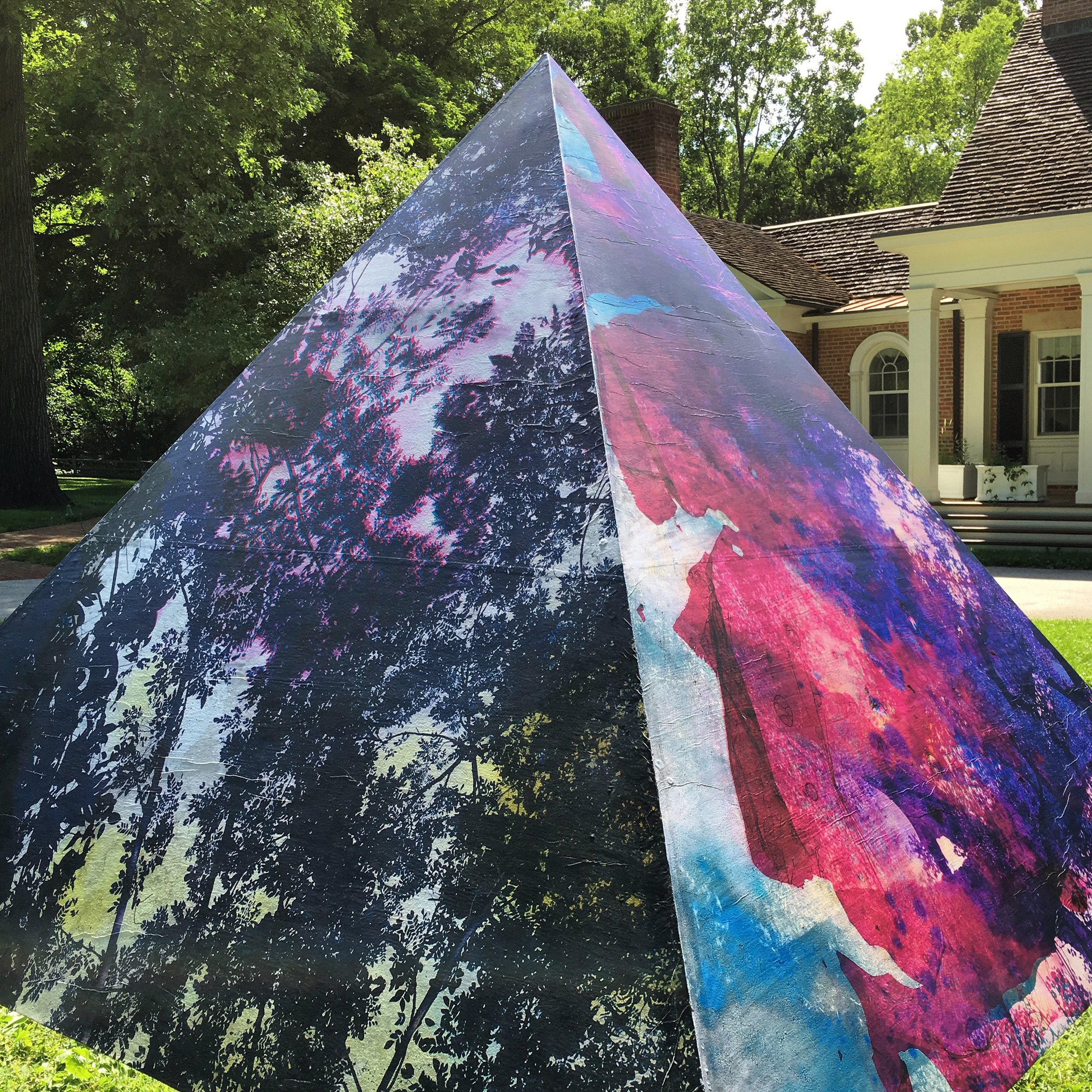

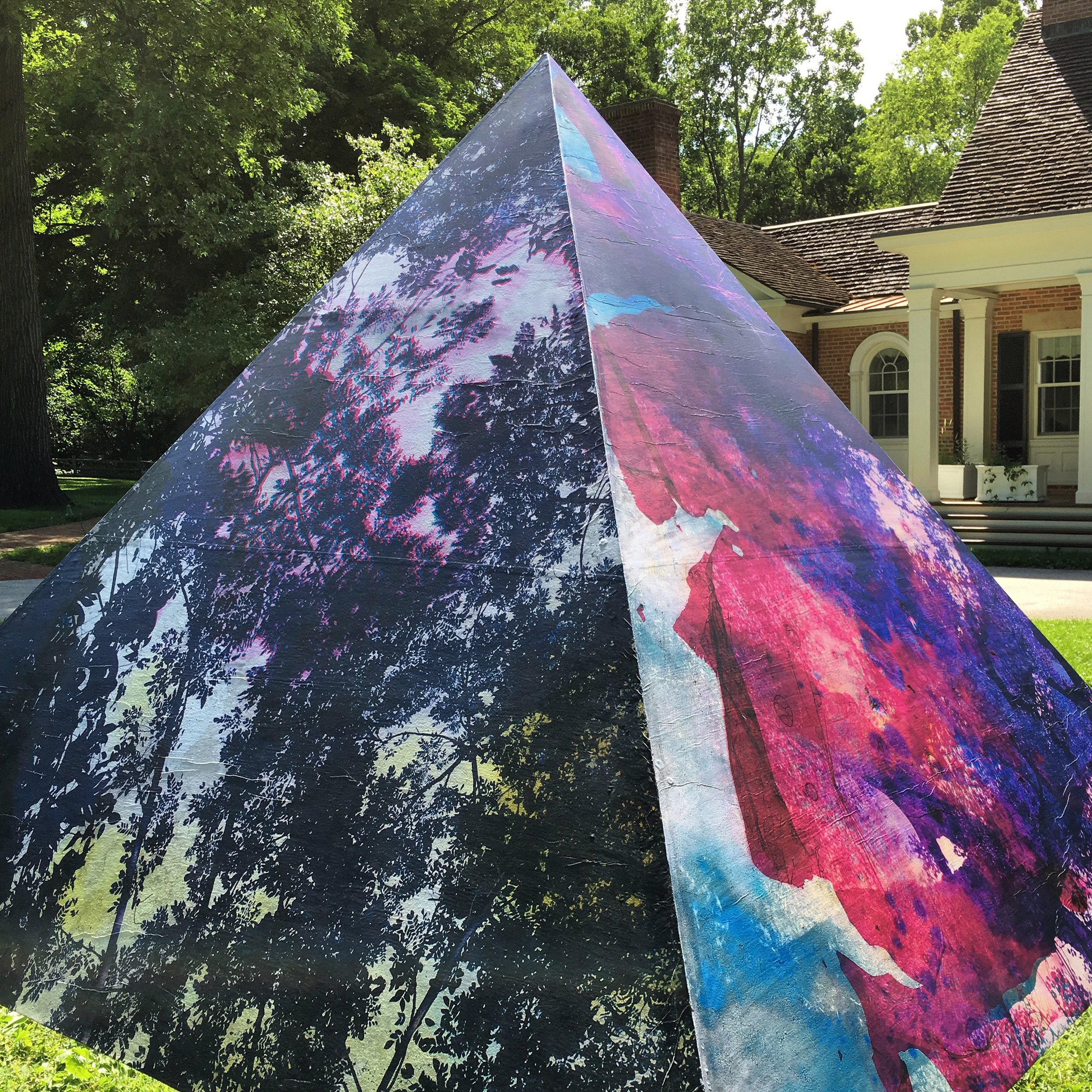

Physis / Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods / Riverwoods, IL

Physis (detail)

Nature Is Dirty / Alpineum Produzentengalerie / Lucerne, CH

Nature Is Dirty (detail)

A Future for Birds and Fish / Alpineum Produzentengalerie / Lucerne, CH

A Future for Birds and Fish (detail)

New Bauhaus Chicago: Experiment Photography and Film / Bauhaus Archiv Museum / Berlin

New Bauhaus Chicago: Experiment Photography and Film (detail)

New Bauhaus Chicago: Experiment Photography and Film (detail)

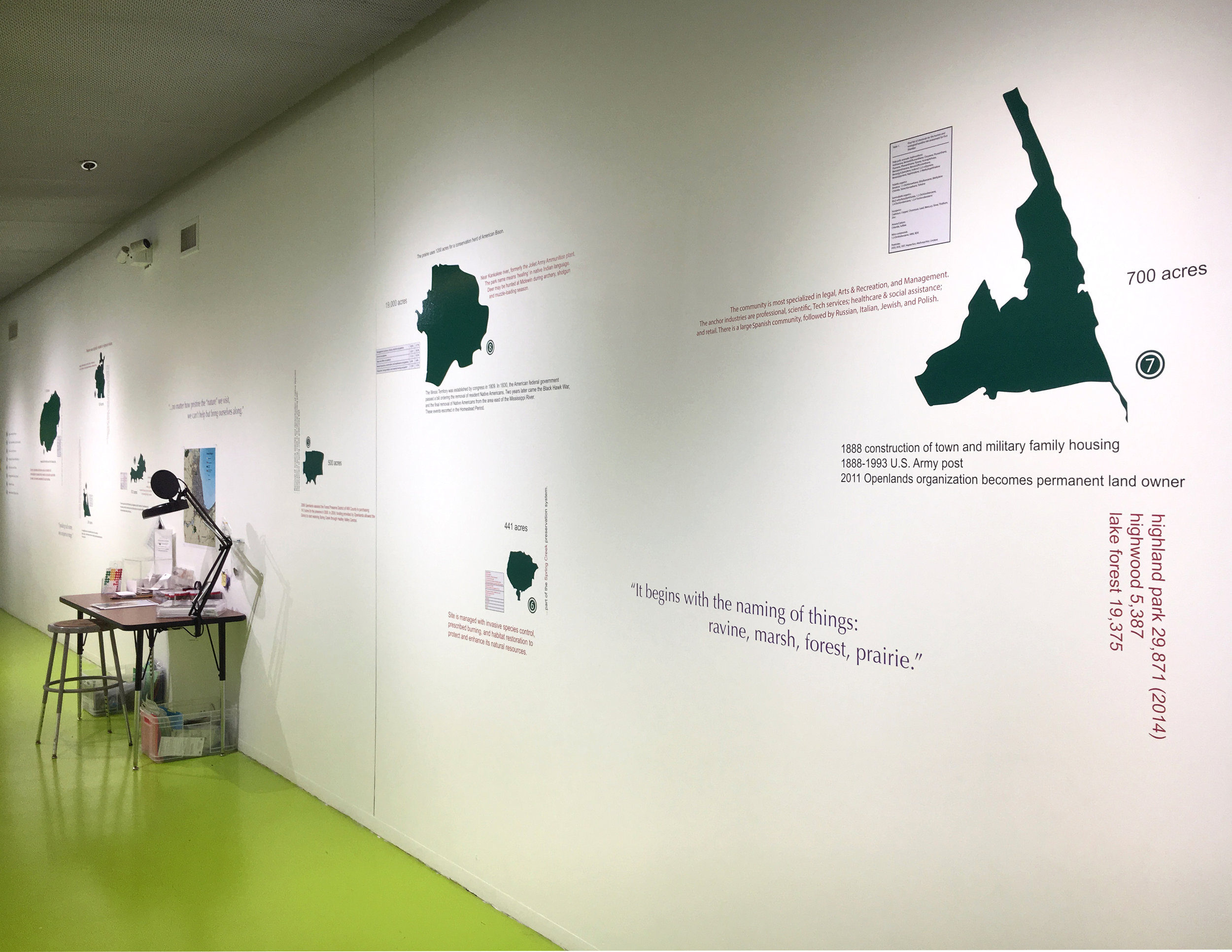

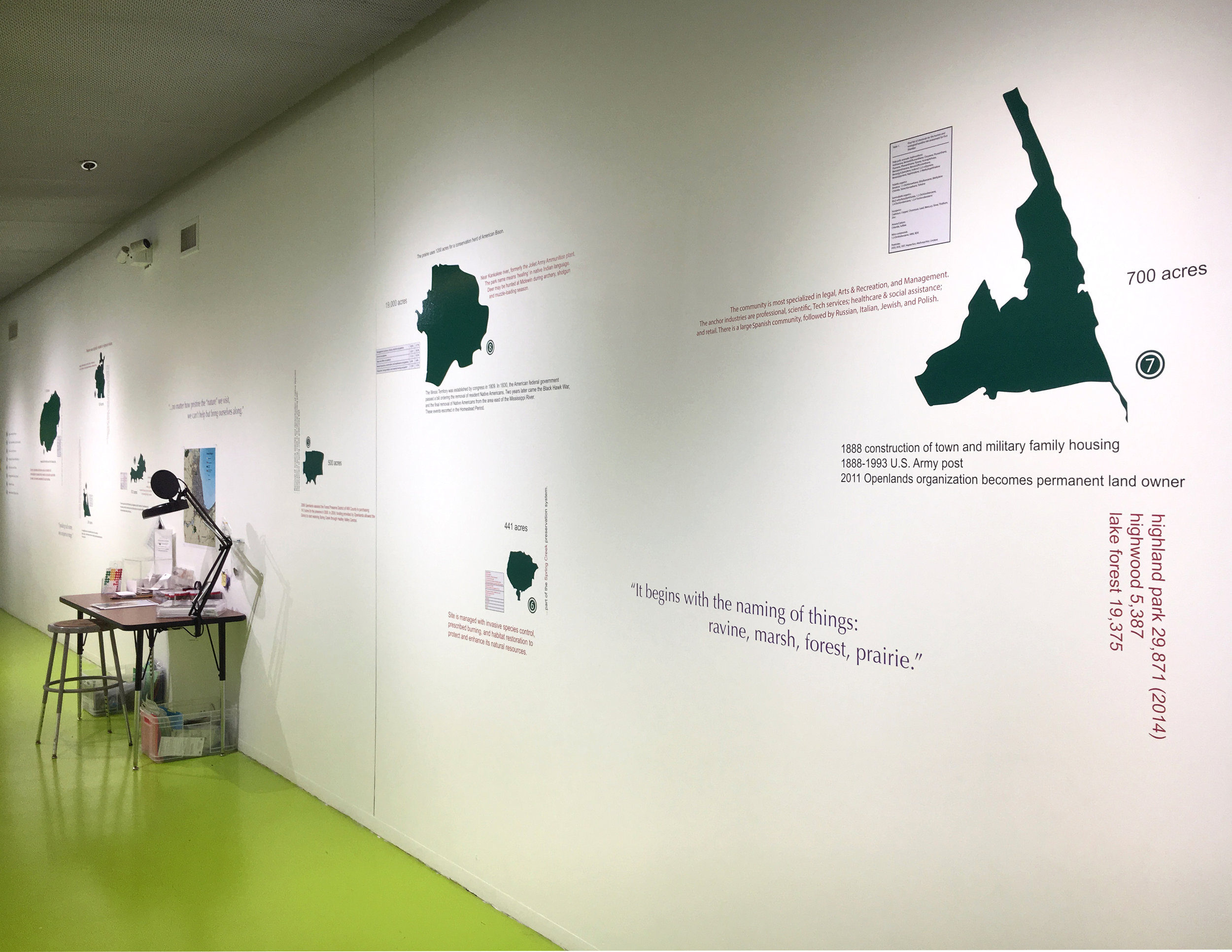

Open Land Art & Fact Team (O.L.A.F.T.) / Hyde Park Art Center / Chicago, IL

Open Land Art & Fact Team (O.L.A.F.T.) / Hyde Park Art Center / Chicago, IL

Study Desk / Open Land Art & Fact Team (detail)

Color Photogram (private residence)

Creative Destruction / Sasha Wolf Gallery / NYC

Creative Destruction / Sasha Wolf Gallery / NYC

Creative Destruction / (reverse view)

Broken Cabinet / Linda Warren Projects / Chicago, IL

Broken Cabinet (detail)

Broken Cabinet (reverse view)

Broken Cabinet (detail)

Broken Cabinet / Elmhurst Art Museum / Illinois

Broken Cabinet / Elmhurst Art Museum (reverse view)

Broken Cabinet / Brushwood Center / Riverwoods, IL

Period (of time) / Wicker Park/Bucktown Public Library / Chicago, IL

Period (of time) / Commission (detail)

Ventura / The Latin School of Chicago (Photographic Wallpaper)

Involution (Adventures in an Ultimate Commonality) / The Latin School of Chicago

Involution (Adventures in an Ultimate Commonality) (detail)

Thriftscape / Chicago, IL

Thriftscape / Chicago, IL / 20 months after install (Sept. '13 - June '15)

Flower Tower / Comfort Station Gallery / Chicago

Flower Tower (detail, six months later)

Terra Cognita / Museum Belvedere / Heerenveen, Netherlands

Exit Eden / Quintenz & Co Gallery / Aspen, CO

Chemical Alterations / SFO Museum / San Francisco

Violet Hour Mural / Chicago, IL

Violet Hour Mural (detail)

Potpourri / Linda Warren Projects / Chicago, IL

Potpourri “Baudelaire’s Fountain” (Day 1)

Potpourri “Baudelaire’s Fountain” (Day 51)

Exit Eden / City Gallery at The Historic Water Tower / Chicago, IL

Field Work / Chicago Urban Art Society / Chicago, IL

Shikako Flag / Field Work

Root No. 2 / Field Work

Study Table / Field Work

Three Billboards / 35th & Ashland / Chicago, IL

Three Billboards / 63rd & State St. / Chicago, IL

Three Billboards / Chicago Ave & Spaulding / Chicago, IL

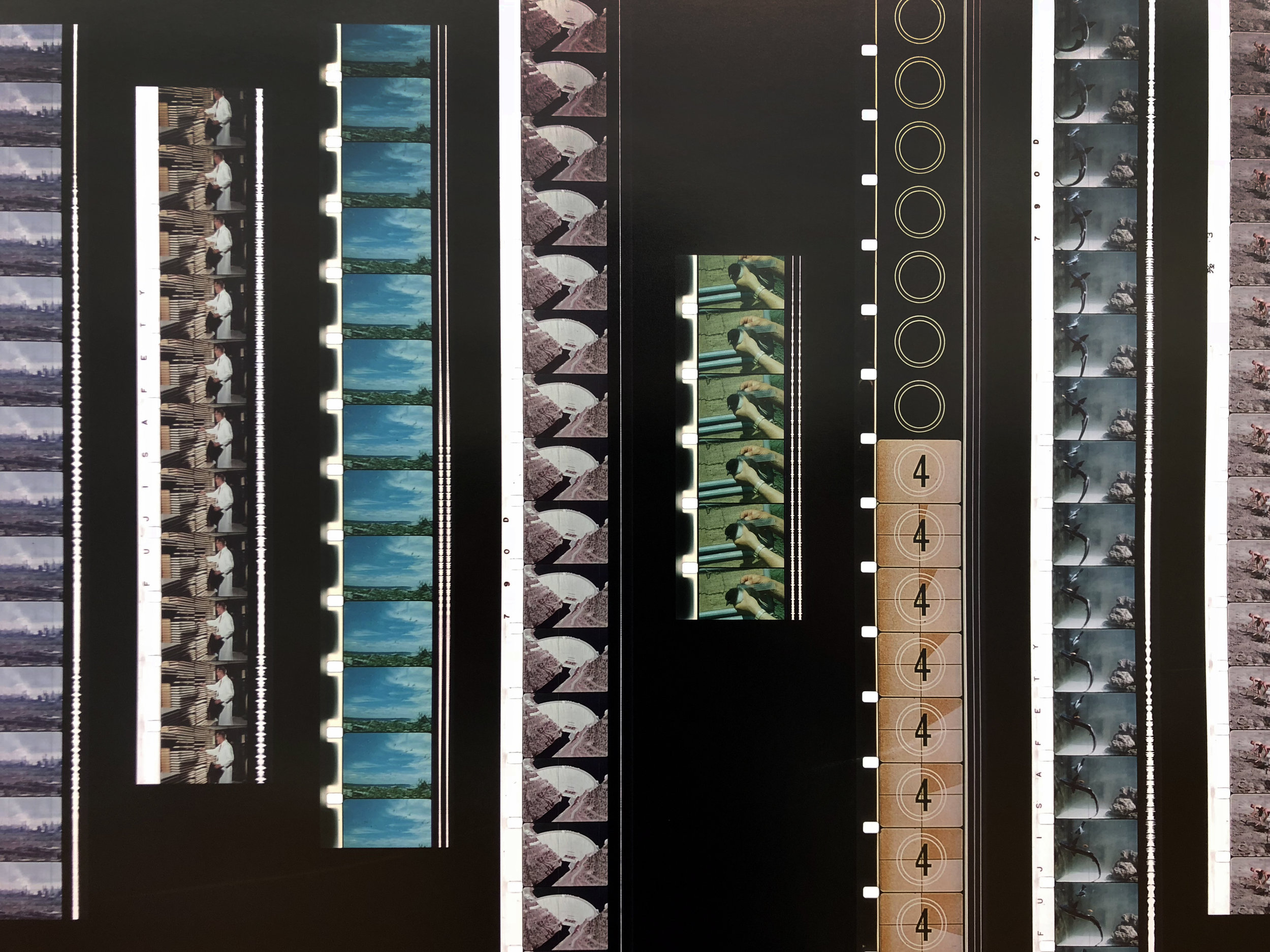

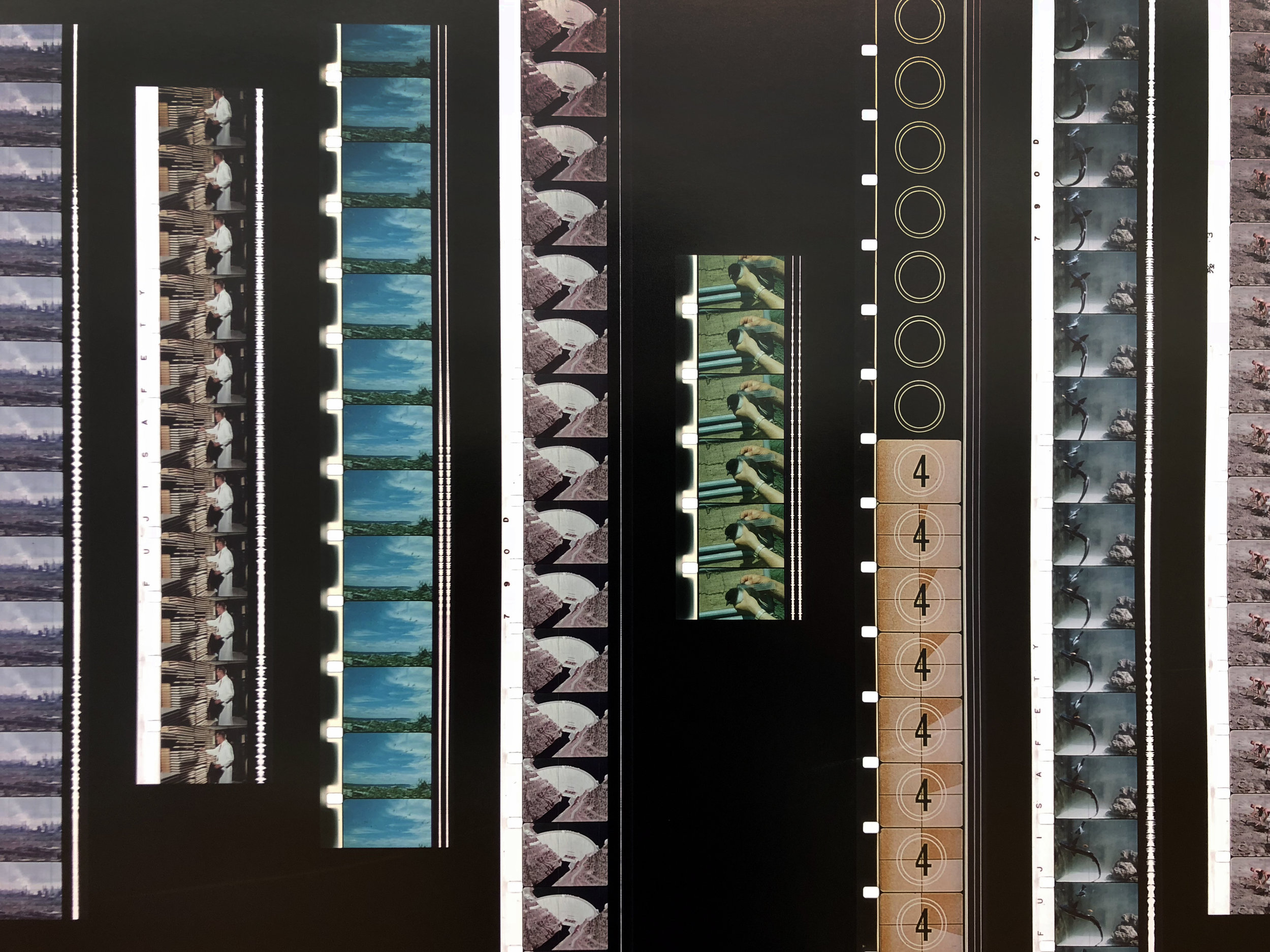

Masters, Edits, and Cuts / Royale Projects / Indian Wells, CA

Masters, Edits, and Cuts (reverse view)

Causa Sui / Daley Plaza / Chicago, IL

Causa Sui / Daley Plaza (reverse view)

Woodland (What is Left Unspoken) / Lubeznik Center for the Arts / Michigan City, IN

Woodland (reverse view)

Castings / Walnut Ink Gallery / Michigan City, IN

Castings (detail)

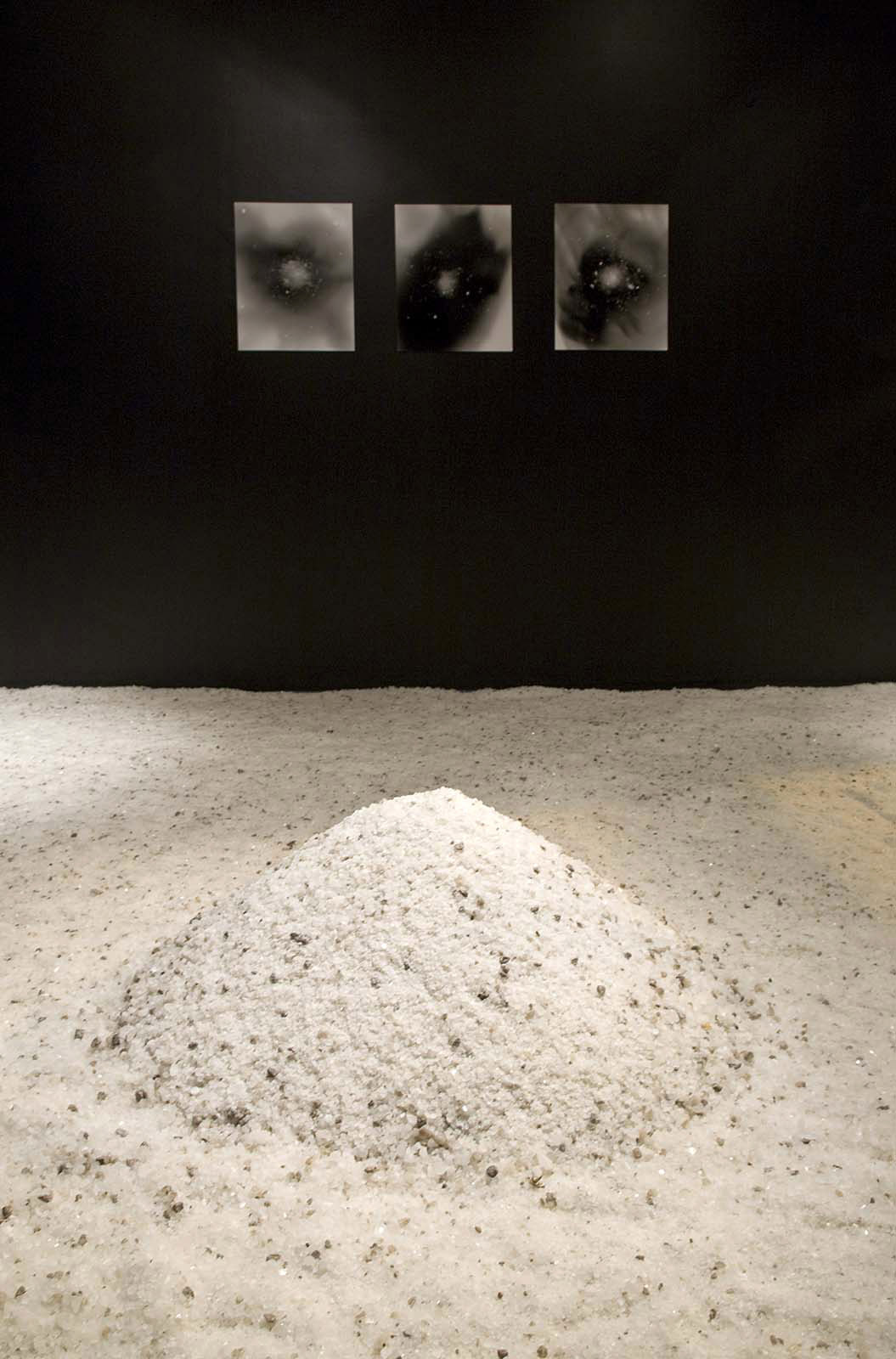

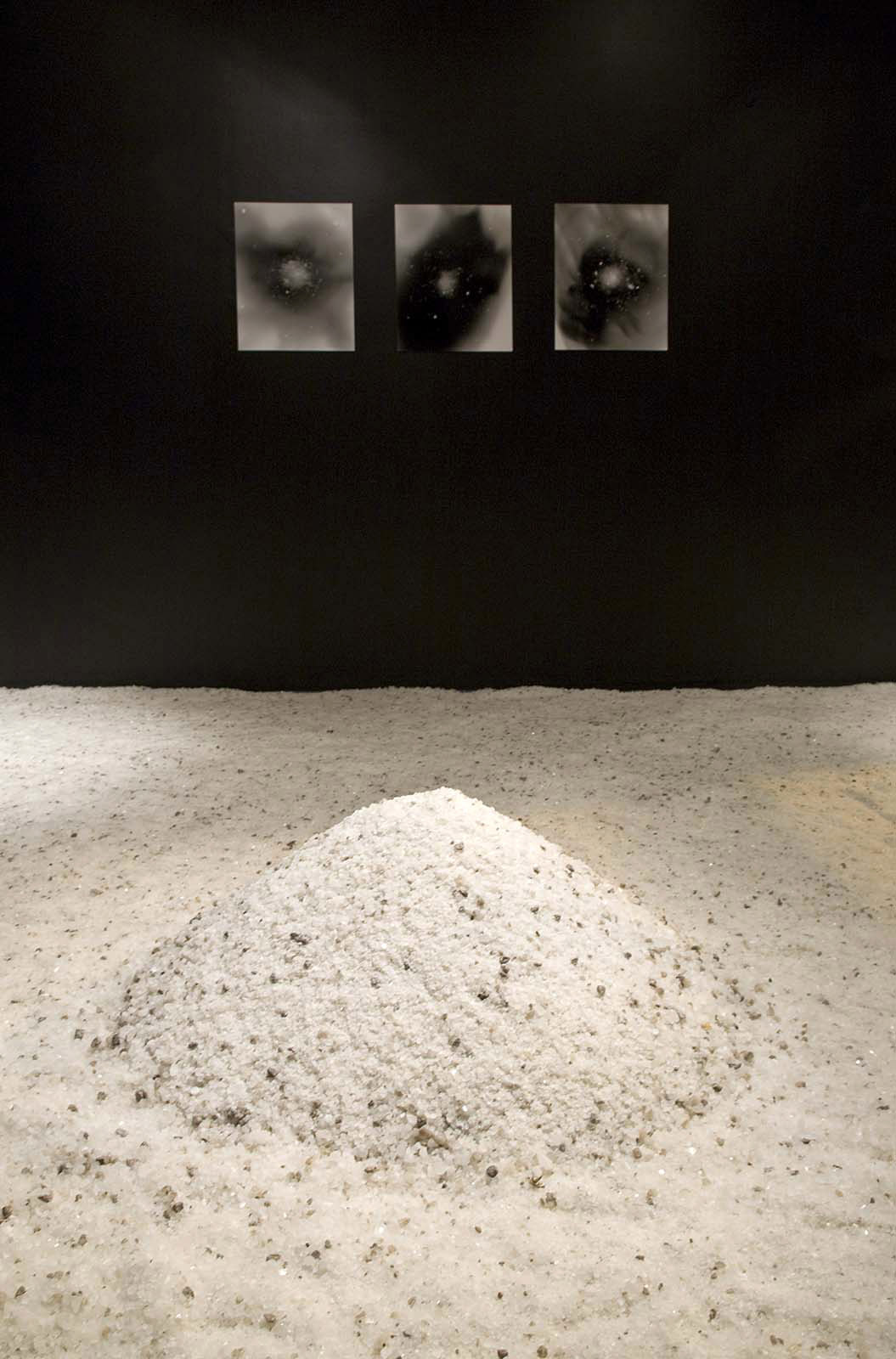

Salt Room (winter on the moon) / Studio 1020 / Chicago, IL

Salt Room (winter on the moon) (detail)

Salt Room (winter on the moon) (detail)

Etheria / Elmhurst Art Museum / Elmhurst, IL

Etheria (reverse view)

Backwash / 300 N. LaSalle / Chicago, IL

Chicago Loop / McCormick Place Convention Center West / Chicago, IL

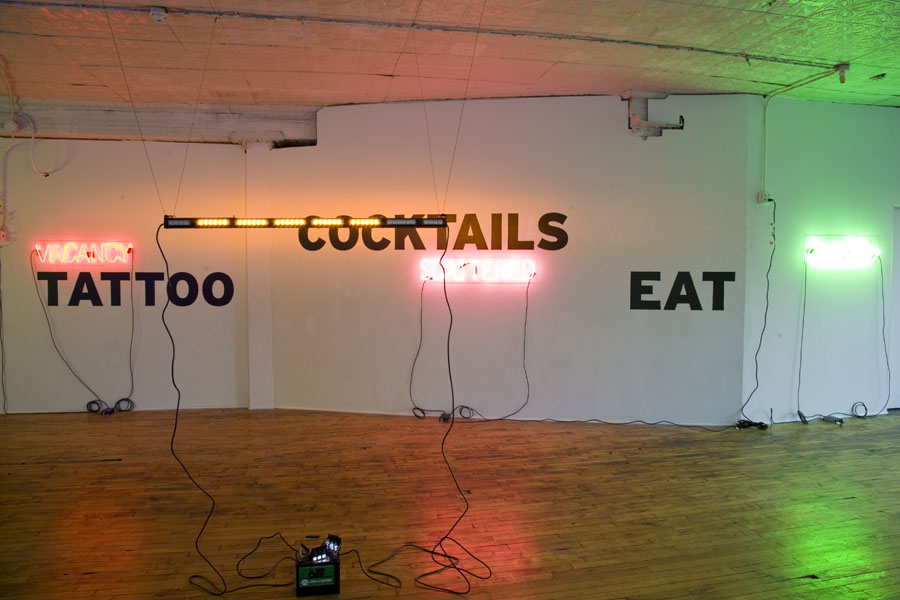

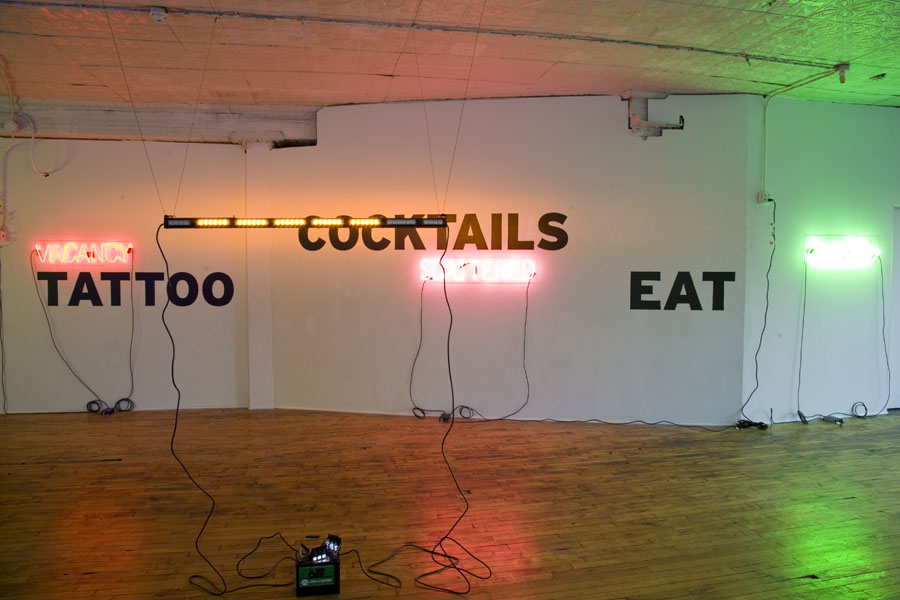

Neon Wilderness (Redux) Room I / Heaven Gallery / Chicago, IL

Neon Wilderness (Redux) (detail)

Neon Wilderness (Redux) Room II / Heaven Gallery / Chicago, IL

Neon Wilderness (Redux) (detail)

Installation / (Private)

"Neil's Branches" / Peter Cooper Village Stuyvesant Town, NYC

Camouflage and Biosemiotics / Hejfina / Chicago, IL

Camouflage and Biosemiotics / Hejfina / Chicago, IL

Stockweave / Skyway Billboard / Gary, IN

Stockweave (context)

Sakura / Lightbox (private)

Sakura / Pagoda Red / Chicago, IL

Signal/Noise Video / Old Friends Gallery / Chicago, IL

Signal/Noise Video (detail)

Terroir / Land + Sky / Oxnard, CA

Terroir / Land + Sky / Oxnard, CA

Terroir (detail)

In The Groves / Land + Sky / Oxnard, CA

In The Groves / Land + Sky / Oxnard, CA

In The Groves / Land + Sky / Oxnard, CA

In The Groves (detail)

Intermezzo / Private Office / Washington D.C.

Intermezzo (reverse view)

Intermezzo (detail)

The Witness / Bert Green Fine Art / Chicago, IL

The Witness / Bert Green Fine Art / Chicago, IL

Watershed / University of Michigan Museum of Art / Ann Arbor, MI

Watershed / University of Michigan Museum of Art / Ann Arbor, MI

Beyond the Frame / Museum of Contemporary Photography / Chicago, IL

Beyond the Frame / Museum of Contemporary Photography / Chicago, IL

Dissolution / Bert Green Fine Art / Chicago, IL

Dissolution / Bert Green Fine Art / Chicago, IL

Sanctuary / 69th Street Red Line Station / Chicago Transit Authority

Sanctuary / 69th Street Red Line Station / Chicago Transit Authority

Sanctuary / 69th Street Red Line Station / Chicago Transit Authority

Anthem / Klompching Gallery / Brooklyn, NY

Anthem / Klompching Gallery / Brooklyn, NY

Reverb / Indiana University Northwest School of the Arts / Gary, IN

Reverb / Indiana University Northwest School of the Arts / Gary, IN

Reverb / Indiana University Northwest School of the Arts / Gary, IN

Nature Now / Lubeznik Center for the Arts / Michigan City, IN

On Plane View / Klompching Gallery / Dumbo, Brooklyn

On Plane View / Klompching Gallery / Dumbo, Brooklyn

Bauhaus und die Fotografie / NRW Forum / Düsseldorf, Germany

Bauhaus und die Fotografie (detail)

Metric 1:50 “Touchstones” / Para Foundation / Berlin

Metric 1:50 Touchstones (detail)

Physis / Brushwood Center at Ryerson Woods / Riverwoods, IL

Physis (detail)

Nature Is Dirty / Alpineum Produzentengalerie / Lucerne, CH

Nature Is Dirty (detail)

A Future for Birds and Fish / Alpineum Produzentengalerie / Lucerne, CH

A Future for Birds and Fish (detail)

New Bauhaus Chicago: Experiment Photography and Film / Bauhaus Archiv Museum / Berlin

New Bauhaus Chicago: Experiment Photography and Film (detail)

New Bauhaus Chicago: Experiment Photography and Film (detail)

Open Land Art & Fact Team (O.L.A.F.T.) / Hyde Park Art Center / Chicago, IL

Open Land Art & Fact Team (O.L.A.F.T.) / Hyde Park Art Center / Chicago, IL

Study Desk / Open Land Art & Fact Team (detail)

Color Photogram (private residence)

Creative Destruction / Sasha Wolf Gallery / NYC

Creative Destruction / Sasha Wolf Gallery / NYC

Creative Destruction / (reverse view)

Broken Cabinet / Linda Warren Projects / Chicago, IL

Broken Cabinet (detail)

Broken Cabinet (reverse view)

Broken Cabinet (detail)

Broken Cabinet / Elmhurst Art Museum / Illinois

Broken Cabinet / Elmhurst Art Museum (reverse view)

Broken Cabinet / Brushwood Center / Riverwoods, IL

Period (of time) / Wicker Park/Bucktown Public Library / Chicago, IL

Period (of time) / Commission (detail)

Ventura / The Latin School of Chicago (Photographic Wallpaper)

Involution (Adventures in an Ultimate Commonality) / The Latin School of Chicago

Involution (Adventures in an Ultimate Commonality) (detail)

Thriftscape / Chicago, IL

Thriftscape / Chicago, IL / 20 months after install (Sept. '13 - June '15)

Flower Tower / Comfort Station Gallery / Chicago

Flower Tower (detail, six months later)

Terra Cognita / Museum Belvedere / Heerenveen, Netherlands

Exit Eden / Quintenz & Co Gallery / Aspen, CO

Chemical Alterations / SFO Museum / San Francisco

Violet Hour Mural / Chicago, IL

Violet Hour Mural (detail)

Potpourri / Linda Warren Projects / Chicago, IL

Potpourri “Baudelaire’s Fountain” (Day 1)

Potpourri “Baudelaire’s Fountain” (Day 51)

Exit Eden / City Gallery at The Historic Water Tower / Chicago, IL

Field Work / Chicago Urban Art Society / Chicago, IL

Shikako Flag / Field Work

Root No. 2 / Field Work

Study Table / Field Work

Three Billboards / 35th & Ashland / Chicago, IL

Three Billboards / 63rd & State St. / Chicago, IL

Three Billboards / Chicago Ave & Spaulding / Chicago, IL

Masters, Edits, and Cuts / Royale Projects / Indian Wells, CA

Masters, Edits, and Cuts (reverse view)

Causa Sui / Daley Plaza / Chicago, IL

Causa Sui / Daley Plaza (reverse view)

Woodland (What is Left Unspoken) / Lubeznik Center for the Arts / Michigan City, IN

Woodland (reverse view)

Castings / Walnut Ink Gallery / Michigan City, IN

Castings (detail)

Salt Room (winter on the moon) / Studio 1020 / Chicago, IL

Salt Room (winter on the moon) (detail)

Salt Room (winter on the moon) (detail)

Etheria / Elmhurst Art Museum / Elmhurst, IL

Etheria (reverse view)

Backwash / 300 N. LaSalle / Chicago, IL

Chicago Loop / McCormick Place Convention Center West / Chicago, IL

Neon Wilderness (Redux) Room I / Heaven Gallery / Chicago, IL

Neon Wilderness (Redux) (detail)

Neon Wilderness (Redux) Room II / Heaven Gallery / Chicago, IL

Neon Wilderness (Redux) (detail)

Installation / (Private)

"Neil's Branches" / Peter Cooper Village Stuyvesant Town, NYC

Camouflage and Biosemiotics / Hejfina / Chicago, IL

Camouflage and Biosemiotics / Hejfina / Chicago, IL

Stockweave / Skyway Billboard / Gary, IN

Stockweave (context)

Sakura / Lightbox (private)

Sakura / Pagoda Red / Chicago, IL